“If you don’t have the infrastructure, you can’t expect people to cycle.”

So states Niels Jensen with austere authority. Niels has been a planner with the city of Copenhagen for 30 years; he was kind enough to spend an hour with our study group and kept us on the edge of our seats.

In a place where most people ride a bike to get around, what’s the story behind their infrastructure success? One thing I’m quick to point out: Copenhagen wasn’t born a bicycle nirvana. It went through a similar cycle of auto-dominated development “progress” that many cities around the world endured. But instead of ignoring warning signs that our economies were too dependent on foreign oil and that we were starting down a dangerous path toward losses in livability and sustainability, they responded. With the bicycle.

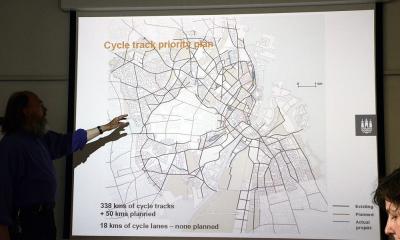

Niels, a city planner in Copenhagen, shows the cycletrack plan

From 1960 to 2008, they built out a vast network of bicycle facilities, including some 200 kilometers of additional cycletrack, that serve all types of riders. This obviously meant investment—and invest they did. The City of Copenhagen reached an inflection point at this time when they galvanized political will and translated it into an immediate tripling of funding for bicycle infrastructure. They spent from $10-20 million each year, and have sustained that commitment to the present day. At about $25 per citizen per year, they have steadily transformed the city into the world-class bicycle city we know today. And it’s a place where bicycling has helped catalyze incredible developments in livability and community that I briefly described earlier this week.

The great thing is that, even though more people bike to work in Copenhagen than any other mode, they’re not done yet. In 1997 their first official plan was adopted, calling for cycletracks on all major roads. Recently, they decided that while 37% of the city—or 155,000 people—ride to work each day, they’re shooting for 50%—roughly 210,000 people each day. Keep in mind that Copenhagen has about the same population as Seattle, although it’s much less diffuse.

Cycletrack in Copenhagen, rush hour

Yet for a city where one can ride from place to place without ever having to mingle on the streets with cars, it’s a big lift to reach another 55,000 people. They might get a few thousand with carrots, says Niels (um, not sure what brand of new carrots they’re imagining, since the place is the world’s leading exporter of beta carotene). They won’t get the rest, however, without a few sticks, he insists. The sticks he mentions are parking policies and congestion charging. But without a nod from the Danish government, Copenhagen can’t brandish these sticks.

Interestingly, the Seattle region has quicker and easier access to sticks than Copenhagen. And the City of Seattle has sustained a yearly $3-4 million commitment to bicycling the last few years. But the political will for the vision of what is possible and for a tripling of this investment—ironically to levels that are spot on to Copenhagen—is tepid.

We have a perception problem.

At a time when our city departments are needing to make substantial and painful cuts—Seattle’s Department of Transportation has to trim about $8 million (14%) this year alone—investment in bicycling is perceived by many to compete with necessary auto infrastructure. Our transit agencies are in serious crisis mode, too. With $157 million less funding each year for the next 4 years, King County metro is considering a 600,000-service hour reduction. So with more ridership on transit than bikes, bicycling is perceived to be less of a priority. And forget pedestrian investments—given $1 billion of needed projects, including 952 miles of sidewalks, we’re going to have to stop walking.

That said, we know that we have a solution. If there’s a time for a simple solution like the bicycle, the time is now. During an economic crisis, many people lose their jobs, lose their benefits or take pay freezes. During this particular crisis, we’re seeing another spike in gas prices. Taken together, owning a car is increasingly expensive, at over $9,000 a year according to the AAA. Many people are looking for ways to save money and other ways to get around. And let’s not forget that 37% of people can’t or don’t drive anyway, many of them for financial reasons. Trade that $9,000 a year of car costs for about $350 a year of bike costs and we have a deal. Add to that the fact that 71% of Americans want to ride more and we’ve got it, right?

Hold on to your pickled herring. Taking a cue from my favorite planner in Copenhagen, I say this with austere authority: we’re expecting people to bicycle but we don’t have the infrastructure.

If we’re going to reach 37% of the population (or even 9%)—including many of the 71% who want to ride more, the people who’d ride but they don’t feel safe or the kids who could easily make the one mile trip to school by bike—we need more. Namely, we need to make a sustained commitment to dream a little bigger, to put down some funding and, in a smart and coordinated way, to not be afraid to use a few sticks to make it happen.

I’d really love to tell my kids some day that we stood on this inflection point in 2011 and didn’t hesitate to transform our cities into great places to live, fit for a Copenhagener like Niels—and, of course, fit for them.